Since the 1960s, Belfast has been a byword for political violence, an unfortunate reputation recently underlined by riots and arson attacks.

Roll back the clock, however, and there is a wealth of achievement to celebrate. Belfast has a rich history in industrial and scientific endeavour – what you might dub, in a word, as progress.

Linenopolis

Belfast’s growth as a city in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century was thanks, in part, to the Industrial Revolution in Britain.

First it was cotton. Belfast entrepreneur and French Huguenot descendant Robert Joy visited Britain in 1777 to find employment ideas for ‘poorhouse’ inmates. Seeing an opportunity in cotton, he copied the innovations of Richard Arkwright and began a water-powered cotton mill. The mill spun cotton thread using the power of the river, automating a process which had previously been laboriously carried out by hand. Things soon took off:

The number of cotton spinning jennies in Belfast had leaped from 25 in 1782 to 229 in 1791. The machine-spun thread was sent to handloom weavers, working in their own homes but paid by the employers; by 1791 there were 522 looms weaving cotton in Belfast… within a 10 mile radius of Belfast, £192,000 was invested in the cotton industry [around £13 million in 2024 prices], which provided work for 13,500 people. The first industrial revolution had arrived in Ireland, and it was in Belfast that it took its firmest hold.1

Belfast’s cotton peak was as late as 1825, with 21 mills employing over 3,500 people.2 They were at the cutting edge of automation and technological deployment at the time. Disaster struck, however, when a six storey mill burned down in an accident, but sensing the economic winds changing, its owners replaced it with a flax mill instead.3 Another British inventor, James Kay, invented a technique that allowed flax, the source fibre for linen, to be likewise spun by machines. Belfast picked the right time to get into this booming industry.

Only two mills spun flax by power in Belfast in 1830 but by 1846 there were 24 mills. Before 1830 all of Ireland exported not more than 4.5 million pounds of yarn a year; from Belfast alone 9 million pounds were exported in 1857 and 28 million pounds in the boom years of 1865.4

In the mid-1860s, the American Civil War led to a drop in raw cotton exports as the southern states were devastated, and Lancashire cotton mills were left unable to spin, leading to a slump in cotton production. Belfast firms took advantage of the resulting boom in linen, cotton’s nearest substitute, utilising new power looms for linen-weaving. The city had 80% of the spindles and 70% of the power looms in Ireland in 1870, cementing its dominance as the ‘greatest centre of linen production in the world.’5

The lesson of the cotton and linen industries is that Belfast can benefit from the innovations of other places, implementing and scaling them up. Railways were similarly built across Ireland at a similar time, another case of importing the best ideas from elsewhere to Belfast’s benefit.

Shipbuilding

Victorian Belfast wasn’t just a one-hit industrial wonder, however. The nineteenth century saw an increase in the volume of global trade and the number of ships, and Britain, still in its imperial heyday, benefitted hugely, increasing demand for ships. At the same time, the shift from wooden shipbuilding to iron saw the UK’s shipping industry – previously spread across the country’s ports – concentrated in Glasgow, Newcastle, Sunderland, and Belfast.6 Shipbuilding thus took over from textiles as the city’s most important export in the late nineteenth century.

Today it’s hard to envisage the sheer scale of Belfast’s shipbuilding industry, employing tens of thousands of men at its peak in enormous drydocks and slipways. The city’s advantage in the industry was borne in large part due to cheap labour, compensating for its relative distance from coal deposits in the north of England. It was aided by various engineering work on the harbour itself, reshaping it, adding channels, docks, and quays, often aided by government support. This process even included land reclamation in 1849, under the supervision of railway engineer William Dargan.

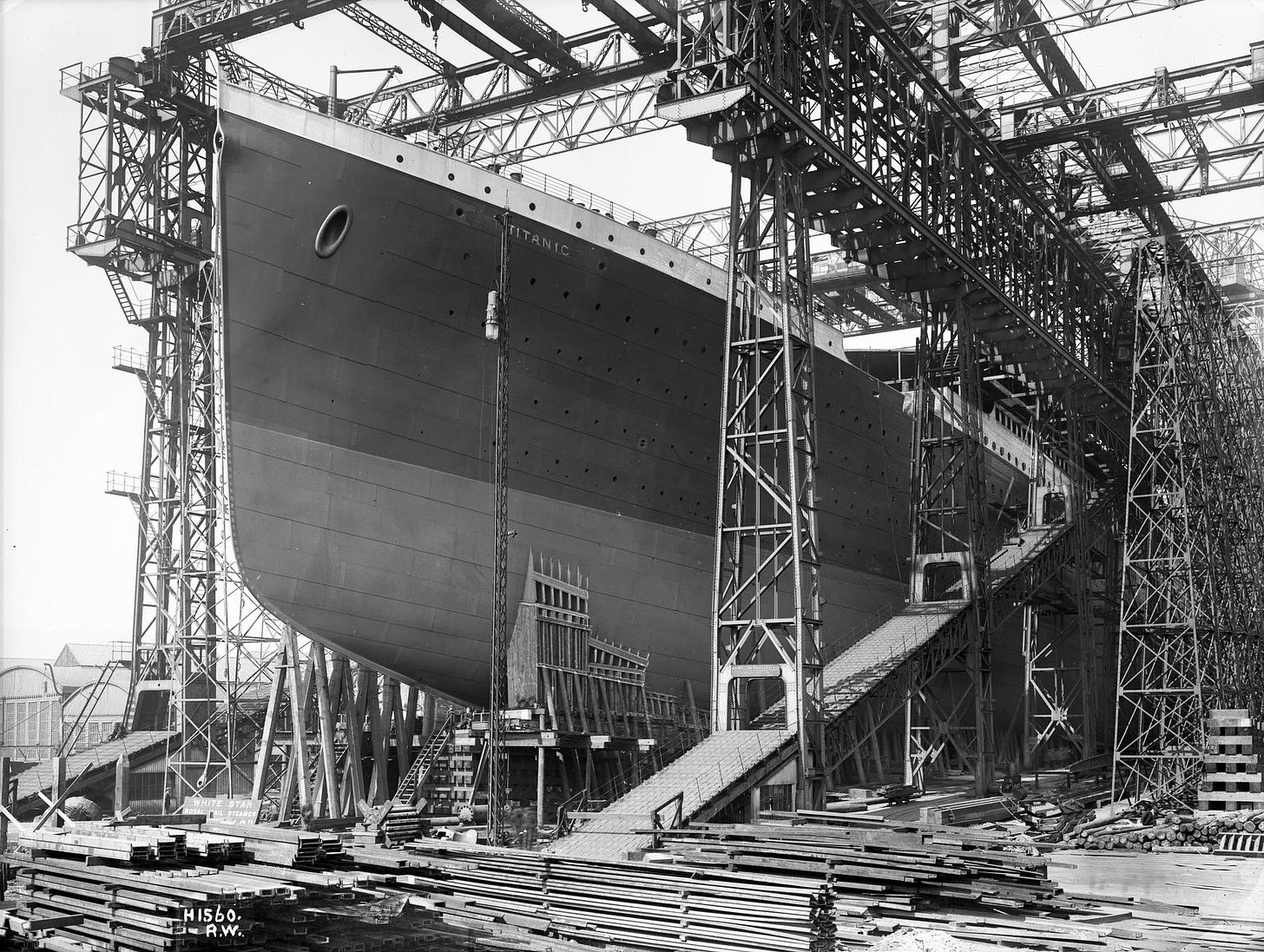

Harland and Wolff was the leading company of its day:

H&W was born out of a small struggling shipyard… which began to trade as ‘Harland and Wolff’ in 1861. In the 30 years that followed, the growth of the company rocketed the shipyard from its original size of 1.5 acres to a new 80 acre site, while the number of employees rose from 100 to 10,000 men.7

Harland and Wolff later built RMS Titanic in 1909-1912. At that point they were the largest shipyard anywhere; as one Belfast historian put it, at the end of the nineteenth century, it was ‘indisputably the greatest shipbuilding firm in the world.’8 Along with another Belfast firm, Workman Clark, they were responsible for a full 8 per cent of global shipbuilding. Considering the importance of ships in the early twentieth century, one could put Harland and Wolff in a similar category to Boeing or Ford today as perhaps the leading manufacturer in a key transport industry. The hype around Titanic and other ocean liners, with crowds gathering to witness their launch, is somewhat reminiscent of a rocket launch today – and Belfast was the leading city for that whole industry.

Success in shipbuilding also helped seed a burgeoning engineering industry in Belfast, from stable house fittings to ventilation and fan manufacturing, and, naturally, the production of spinning and flax machinery as well as agricultural machinery.9 John Boyd Dunlop, a veterinary surgeon, invented the first working pneumatic tyre in Belfast, and started a tire brand which still exists today. The parallels to Los Angeles’s growing hardtech startup scene today – downstream of SpaceX – are obvious.

Belfast’s shipyards later faced a decline similar to those of another British imperial city, Glasgow (not to mention similar declines in Sunderland and Kent). Today H&W employs only a fraction of the men it once did, and faces financial difficulties. The twenty-first century’s largest shipbuilding companies are almost entirely based in East Asia, where other countries have used the industry as an economic stepping stone much as Belfast (and the UK) did.

The textiles lesson – importing innovations from other places – certainly applies in this shipbuilding context too. But there are others: like its cotton and linen, Belfast exported these ships abroad, making something that the world really wanted.

The success of firms like Harland and Wolff was also driven by ambitious entrepreneurs – exactly the kind of spirit behind the most fast-growing and valuable companies today. Samuel Smiles, author of nineteenth century bestseller Self-Help, cited the wealthy Harland as an example of the rewards to hard work.10 (Harland even contributed a chapter to one of Smiles’s books.)

An underlying lesson is that great things are possible; Belfast’s coastline was literally reshaped to boost the shipbuilding industry.

Science, knowledge, and small groups

Belfast’s endeavours in the Victorian era also extended to intellectual spheres.

Take, for example, the Belfast Natural History and Philosophical Society, founded in 1821. Its eight founding members leveraged Belfast’s increasingly international connections to begin collecting antiquities and natural history specimens from around the world. This later culminated in the opening of the Belfast Natural History and Philosophical Society Museum – Ireland’s first purpose-built museum – in 1831, thanks to a large donation from the city’s merchants and public subscriptions.11

The Society’s members were also involved in the establishment of the Botanic Gardens in 1828. John Templeton, the 'father of Irish botany', was a key promoter of the project. An infovore who was focused on the natural world, he was the first to catalogue a range of Irish species, and corresponded with the leading botanists of his day. Later, in 1889, Charles McKimm, head gardener in the Gardens added a Tropical Ravine. Today it includes a temperate zone, with lots of ferns in particular, and a more tropical area, holding plants that wouldn’t otherwise survive in Ireland’s climate:

The collection of plants that is grown in the Tropical Ravine is based on a 1904 plant list. Some of the plants inside, for example the cycads, are over 200 years old and endangered in their native habitat. The tropical ravine is where the giant waterlily, Victoria Amazonica, was grown in Ireland for the first time in 1852 and is still planted each year. The banana stumpery has been there from the early 1900s and the bananas were used to feed patients in Musgrave Hospital during the First World War.12

The Tropical Ravine was extended with a second section in 1900. This section was kept warmer than the original ravine and used for tropical plants rather than temperate species. Another extension was built in 1902 to install a heated pond to grow the giant water lily from South America. These alterations added 76 feet in length to the Tropical Ravine.13

Plant species include the Killarney fern, orchid, banana, cinnamon, bromeliad and some of the world’s oldest seed plants.

There were many other nineteenth century societies including: the Industrial School, the Literary Society, the Cosmographical Society, the Belfast Medical Society, the Mechanics Institute, and the Female Society for the Clothing of the Poor.14 This non-exhaustive list hints that those societies which were not scholarly were instead focused on the improvement of society.

And let’s not forget the Belfast Society for Promoting Knowledge, founded in the late eighteenth century body aimed at the ‘collection of an extensive Library, philosophical apparatus and such products of nature and art as tend to improve the mind and excite a spirit of general enquiry.’ Today it is known as the Linen Hall Library – the oldest library in Ireland – and still operates on a partly subscription-based model.

Belfast residents happily formed these groups in an era when the average person was much less educated, and vastly fewer resources were directed towards universities and research.

Today

In 2024, Belfast is definitely on a positive trajectory, with increasing tourism and growing employment in the financial services industry especially. There is cause for optimism.

Yet the city is some way off its peak, as the examples above indicate. There isn’t the same ferment today, a focus on improvement and development – a fixation on progress. Belfast has ample reason to be ambitious, improving on its current standing in the world by importing the best ideas and technologies from around the world, scaling them up. Its storied history shows it can be done.

If you are interested in a Belfast-based reading group focused on economic growth and scientific progress, please reply to this email, comment below, or send me a DM on Twitter.

Jonathan Bardon, Belfast: An Illustrated History, 44-45.

Bardon, 70.

David Dickson, The First Irish Cities: an eighteenth century transformation, 242.

Bardon, 117.

Bardon, 117 & 123.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/24337415

https://www.titanicbelfast.com/history-of-titanic/titanic-stories/a-history-of-the-shipyard-queen-s-island-to-titanic-quarter/

Bardon, 152.

Bardon, 132-133.

Bardon, 129-130.

Bardon, 83.

https://www.belfastcity.gov.uk/things-to-do/tropical-ravine/visiting-the-tropical-ravine#1159-1

https://www.belfastcity.gov.uk/things-to-do/tropical-ravine/history-of-the-tropical-ravine#1155-1

Bardon, 83-84.

Fergus- I love learning about cities other than my own here in America. So it’s great to get insights from those across the pond. Especially when you mentioned: “Yet the city is some way off its peak, as the examples above indicate. There isn’t the same ferment today, a focus on improvement and development – a fixation on progress.” I appreciate you sharing this.