Observers of American culture and politics soon become aware of the Bible Belt, a swathe of southern states with a strong adherence to evangelical Christianity. Less known is that the UK has its own corresponding Bible Belt, in Northern Ireland. Its epicentre is Ballymena, my hometown.

The American Bible Belt has a high share of adults who believe in God, and a high share (50% or more) who report that religion is very important. Data for Northern Ireland in general is spottier, but anecdotally, those figures probably replicate.

The theology in both Bible Belts is decidedly conservative and evangelical. That means that there is a strong emphasis on the Bible, the importance of conversion, the atoning work of Jesus on the cross, and a global mission of sharing Christianity with others.

Both regions also have a history of revivals, i.e. periods when there is a sudden increase in the number of Christians, often linked to large public gatherings. Going to a public gathering where someone speaks about the Bible is socially normal in the Bible Belt, but might be unheard of elsewhere.

Scale and money

The genuine differences between the two are more subtle. First, the market in churches in Northern Ireland is a lot shallower – people often simply go to the church their parents went to, or have enough ties to a church that they won’t switch. People like to live near where they grew up and don’t move away particularly often. For example, there are war memorials in the church I grew up in – the surnames on the wall are the same surnames that you’ll find among the attendees today. It’s hard to argue that a new church is needed, let alone make it work in practice.

The fact that there are fewer new churches in Ballymena means that change is much slower. For better or for worse, teaching and style of delivery can resemble what it did decades ago, and older buildings are less amenable to fancy lighting and smoke machines. This is also a question of money (more on that below).

Charismatic churches are still very much the minority in Ballymena, again partly a result of fewer new churches. There are other important factors here too though: Ulster Protestants aren’t known for their expressiveness, especially compared to Americans, so charismatic practices such as concert-like services and speaking in tongues are plausibly less of a fit than in the U.S.

In the American Bible Belt, by contrast, there are dozens of new churches. For whatever reason – shallower family roots, consumer mentality, social changes, ambition, moving home – Americans are generally happy to switch between churches, so there is a ready constituency who will happily go along to a new church. Growing sunbelt cities have been a great opportunity for new churches, with Rick Warren’s Saddleback church one of the most prominent examples.

However, the most important single difference between the two areas is money. There is significantly more wealth in the U.S. than in Northern Ireland. In a church context, this is worked out in the size of church staff (effectively always multiple full time staff members), the size of church buildings, staff salaries, and the general wealth of each church.

In the U.S., while this money often goes to evangelistic work or foreign aid (as it does in Northern Ireland), it also gets spent locally. For example, one of the bigger churches in Tulsa, Oklahoma – a leading city in the U.S. Bible Belt – recently bought an office building for $35 million.

Megachurches are quite common in the U.S. too. With attendees in the multiple thousands, they tend to have concert or broadcast levels of production and media, and their pastors are often very influential in American Christianity. Joel Osteen’s church, for example, hits 45,000 visitors a week.

In Ballymena, churches have enough money, but their attendees are not particularly well off. There are few rich businesspeople who can sustain extremely ambitious projects, despite generous giving by the rank and file. As a result, the churches tend to be small (500 attendees would be on the larger end), and don’t tend to have more than one staff member.

The megachurch model doesn’t work in Northern Ireland. One Ballymena church tried to do this – it built a large, brand new building at the edge of a town, partly funded by a growing congregation but also by the family of the pastor, who ran a profitable manufacturing business. However, they eventually ran out of money, haemorrhaged attendees, and seem to be struggling to complete the building.

Alike in dignity

Perhaps the most important underlying similarity between the two regions is, in fact, the people who live there. The distribution of Scots-Irish overlaps with the U.S. Bible Belt, a population that was drawn from Ulster in the eighteenth and nineteenth century. These Scots-Irish, like their cousins in Northern Ireland, have an honour-based culture, where personal insults are often resolved through physical violence. They might be more Baptist than Presbyterian nowadays, but the underlying theology remains evangelical in character.

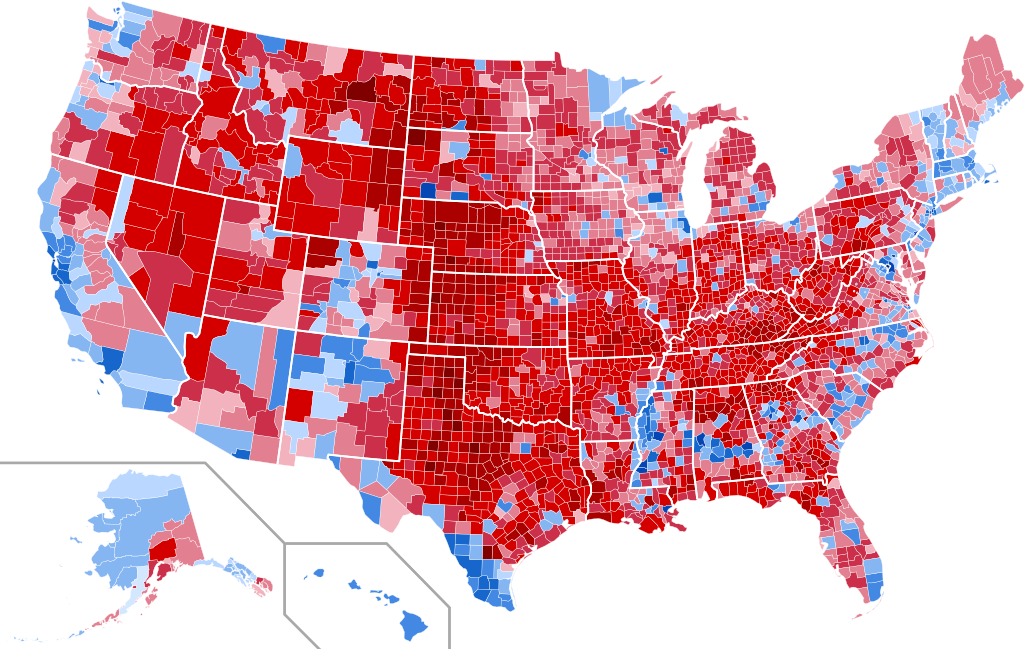

This brings us neatly to contemporary politics. The Bible Belt states voted for Trump in 2016 (see the map) and 2020, and will do so again in 2024. For what it’s worth, the affection for Trump is replicated in parts of Northern Ireland too:

Northern Ireland has its own religious-political complex, but it’s worth noting that in both countries, politics is as much a cultural competitor with religion as it is an expression of it.

Take J. D. Vance, Trump’s VP pick. He’s from Kentucky, and explicitly acknowledged his Scots-Irish ancestry in the opening of his memoir. Aaron Renn recently dug out this 2016 comment by Vance:

Vance: The second thing is that we tend to think of these areas as the Bible Belt, where everyone is going to church and everyone is actively involved in religious community. That’s not that true.

If you look at the statistics and see some of the things I’ve seen, you recognize that these people, despite being very religious and having their Christian faith as something important to them, aren’t attending church that much. They don’t have that much of a connection to a traditional religious institution.

Religion is important. That conception is right. But religion is quirky, and it’s not traditionally practiced in religious institutions.

Religious adherence might be deep in the culture, but not in the modern practice of Americans in the Bible Belt. Politics helps keep religion salient as a form of identity in Northern Ireland, but that might change too.

Fundamentally, both groups are unhappy by disposition, happiest when they are complaining (I cherish this curmudgeonly attitude, which I personally share. It’s accompanied by personal warmth and hospitality). The American Bible Belt has, for better or worse, found a champion fit for the 21st century in the form of Donald Trump. He expresses their discontent. Their cousins in Northern Ireland, as yet, have no equivalent.

"Fundamentally, both groups are unhappy by disposition, happiest when they are complaining. "

This in a nutshell. And really, how sad.

Nice specific piece Fergus